The ‘Glorious Thirties’ were characterised by strong economic growth, full employment, rapid increases in purchasing power and the rise of mass consumption.

This industrial, scientific and technical transformation was manifested mainly in the use of new energy sources, the development of automation and, finally, in the chemical industry, a series of discoveries and developments that enabled the production of a growing number of synthetic products that could, in the future, largely replace the major natural products, metals and, no doubt, natural foods.

Thanks to the tenfold increase in power brought about by this wave of discoveries, the scope of human activity is beginning to extend to the conquest of space.

At the height of these three decades of economic growth, industrial production intensified, and each French citizen generated an average of 250 kilos of waste per year in 1960. A figure that would only increase over the years as consumption steadily rose.

But at that time, new waste also meant new problems.

After decades of systematic ocean pollution, the 1972 London Convention prohibited the dumping of certain hazardous wastes, such as industrial sludge and radioactive materials.

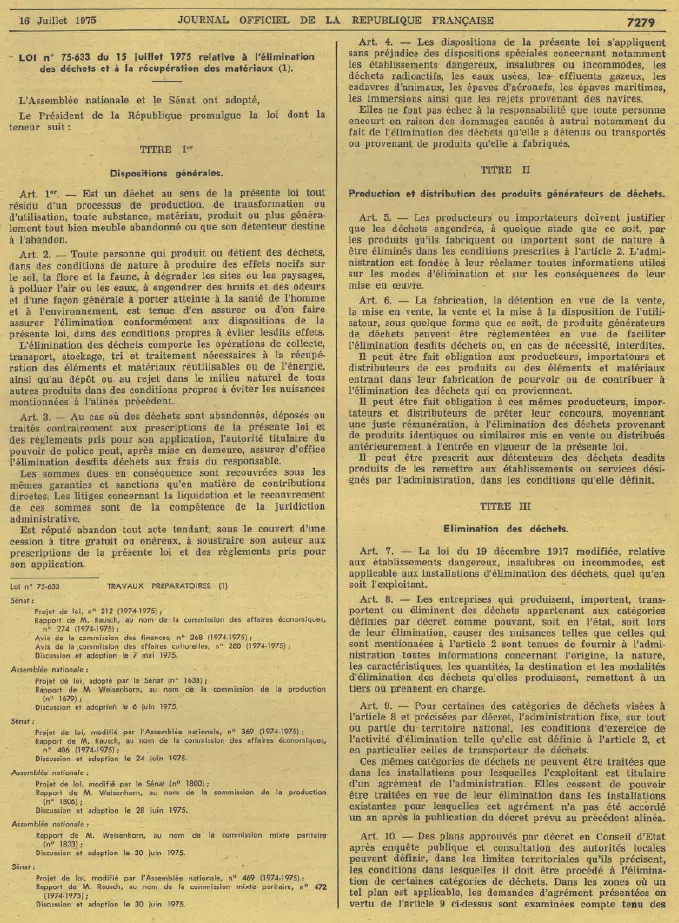

The 1975 law gives waste legal status and sets out the responsibilities of all waste producers.

Waste is defined as ‘any residue of a production, transformation or use process, any substance, material, product or, more generally, any movable asset that is abandoned or that its holder intends to abandon’.

The polluter is the person who ‘produces or holds waste under conditions likely to have harmful effects on the soil, flora and fauna, to degrade sites or landscapes, to pollute the air or water, to generate noise or odours and generally to harm human health and the environment’. He is held responsible for his waste and is obliged to dispose of it, or have it disposed of, in conditions that respect health and the environment.

In response to the regulatory requirement for industrial companies to have their waste treated in dedicated facilities, SARPI was born, with the inauguration of the first plant in July 1975.

The first static incinerator was commissioned in 1976.

Other plants were added to SARPI's network of treatment facilities in France and Europe.

In 2024, SARPI employs more than 4,000 people and has more than 110 industrial sites in 10 European countries.

Until the end of the 20th century, the priority was to eliminate waste and control its toxicity by incineration or landfill.

At that time, recovery and recycling were not yet firmly established in the industry.

Under the pressure of climate change and growing environmental awareness, the early 21st century saw the emergence of waste sorting and the ambition (or necessity) to recover waste in the form of materials or energy in order to preserve natural resources.

Sorting waste to produce secondary raw materials means neutralising the toxic fraction contained in order to guarantee pollution-free secondary materials.

This is what is known as decontamination of the recycling loop, coupled with the notion of complete traceability of the waste taken in charge.

Developments in industrial materials and new regulations are constantly leading to the creation of new treatment and recovery processes (oils, solvents, vaccine adjuvants, medicines, hydroalcoholic gel).

At the end of the chain, incineration and/or storage of final waste that cannot be recycled are still necessary to contain pollution.

In the face of the climate emergency and the need to preserve natural resources, recycling is no longer enough.

We now need to close the recycling loops by producing new raw materials that meet or exceed the standards of the initial materials used in industrial production.

This is not only an environmental and social priority, but also an issue of economic independence for territories and continents (strategic metals, etc.).

New forms of know-how alliances between manufacturers are already accelerating this process.

Since its creation, SARPI has supported these environmental and industrial changes.

Its network of dedicated facilities enables it to treat all types of pollution without dilution.

Its activities are necessary and useful in tackling the ecological emergency:

by neutralising yesterday's and today's pollution, by guaranteeing the traceability and decontamination of recycling loops, by producing new raw materials for a new production cycle, thus helping to reduce the CO2 impact of human activities and industrial production.